THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT - DOCUMENTS AND EVENTS

Various documents mentioned below shed light on the prehistory and history of the Angles, the Wicken, the Hwicce, and the Wickendens. They provide a context within which the story of the Wickendens can be better understood. They are listed below in five sections: I. The Origin of the Angles, II. The Anglo-Saxon Settlement of Britain, III. The Norman Conquest, IV. English History, and V. American History. The relevance of each event to the Wickendens is summarized in an underscored paragraph at the end of each section.

I. THE ORIGIN OF THE ANGLES [This commentary is adapted from several sources including the Wikipedia article on the topic, accessed in June 2020.]

Early References to the English [This information is adapted mostly from Peter Hunter Blair, Anglo-Saxon England, An Introduction.]

The earliest reference to the English is in the Germania of Tacitus (AD 56 – c. 120, a Roman historian and politician) where, under the name Anglii, they are described as being one of a group of seven tribes who worshipped a goddess called Nerthus at an island sanctuary. It may be inferred from this passage that the Anglii were a seaboard people, though the passage itself does not reveal whether the island on which the sanctuary of Nerthus lay was in the North Sea of the Baltic. There is a conflict of evidence between Tacitus and Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170, a Greek mathematician and geographer living in Alexandria in the Roman province of Egypt) who regarded the Angles as an inland people and located them to the west of the middle Elbe. Most scholars are, however, agreed that Ptolemy was here in error. A fragment of tradition preserved in the Old English poem Widsid refers to Offa, a king of Angel, establishing the boundary of his kingdom by a river called Fifeldor. This is thought to be a name by which the River Eider was once known. The evidence of Widsid, combined with that of Tacitus, Bede and Alfred, justifies the belief that the English lived in the southern part of the Jutland pennsula before they migrated to Britain. The name of their homeland, which Bede calls Angulus, seems to be preserved in the provincial name Angeln applied to the area north-east of Slesvig" (Blair, p. 7). So the question remains as to whether the Angles were inland people in northern Germany or in southern Jutland or were sea-going people living along the shore of the North Atlantic or on one or more of the Frisian islands.

The Migration Period - The early Anglo-Saxon period covers the history of medieval Britain that starts from the end of Roman rule. It is a period widely known in European history as the Migration Period, a time of intensified human migration in Europe from about 375 to 800 of Germanic tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, Angles, Saxons, Lombards, Suebi, Frisii, and Franks. They were later pushed westwards by the Huns, Avars, Slavs, Bulgars, and Alans. The migrants to Britain might also have included the Huns and Rugini. The Wicken may then have been one of many extended family groups or clans of Angles who were among those pushed westwards during the Migration Period.

It is important to understand that although several authorities recognize the separate existence in early times of Angles, Saxons, and Frisians, and in some degree also of Jutes, it is probable that the great movement of peoples during the Migration Period, did much to lessen racial distinctions, particularly when the crossing of a sea was involved (Blair, p. 10). For example, Fisher notes that although the Germanic tribes were pressured ultimately to cross the North Sea to Britain, rowing in small open boats without sails and navigational aids, these adventurers would seek to make their North Sea crossing as short as possible and so would hug the land until this was achieved. Hence while there is evidence that Frisia experienced a large-scale migration of Saxons in the first-half of the fifth century, their descendants moved on again after a landfall of indeterminate duration on the Frisian coast (Fisher, p. 23-24).

Also, is it not apparent why the people called Engle in Old English and Angelii by Latin writers gave their name to the country which they came to inhabit. There is no evidence to suggest that they were more numerous than the other immigrants or that they took a particularly prominent part in the invasions (Blair, p. 11). Finally, there were multiple family groups, clans and tribes at this time who were on the move. The Angles (and the Wicken) appear to have moved first to Angeln in the north, then perhaps up onto the Jutland peninsula, then down the coast by boat and/or inland by foot, for an indeterminate stay on the Frisian coast, perhaps even farther south toward the Franks in Gaul, and finally over to Britain. Various observers may have observed the Angles at different times, and therefore have reported them in different locations, as they moved from point to point . The place-names derived from the Wicken appear to indicate this kind of movement (see the page in this section on From Wickendorf to Wickenden) as they include many locations mentioned in these historical documents.

Success and Survival of Tribes

If the evidence presented in this website is correct, it suggests that the Wicken may have forged an extended kinship group early in the Migration Period and successfully maintained their coherence and identity over several centuries and through many movements and resettlements, including crossing the channel and participating in the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain. C. Warren Hollister notes that Germanic peoples devoted themselves chiefly to tending crops or herds, fighting wars, hunting, feuding and drinking beer. ...Women played important roles in Germanic communities, performing much of the agricultural labor and sometimes joining in the traditional male pursuits of hunting and warfare [not to mention their role in bearing and caring for children!]. ...A tribe's success depended heavily on the ability, reputation and charisma of its leader, a chief or king. A successful king was one who led his warriors to victories that won them rich plunder, and who used his own war booty to reward his loyal followers with lavish generosity. ...The most honored profession was that of the warrior, and the warlike virtues of loyalty, courage, and military prowess were esteemed above all others.

The chief military unit within the tribe was the war band or comitatus, a group of warriors or "companions" bound together by their allegiance to the leader of their band. ...Another, much older subdivision of the tribe was the kin group or clan. Members of a clan were duty-bound to protect the welfare of their kinfolk. Should anyone by killed or injured, all close relatives declared a blood feud against the wrongdoer's kin. Because murders and maiming were only too common in the violent, honor-ridden atmosphere of the Germanic tribe, blood feuds were a characteristic ingredient of Germanic society.

We know nothing about the leaders of the Hwicce until the advent of the Kingdom of Hwicce. Needless to say, simply by their persistence throughout this era, they have demonstrated an extraordinary ability, reputation and charisma to keep internal feuding to a minimum, to fiercely protect the welfare of Wicken kinfolk, and since the Wicken appear to be somewhat smaller in number than their neighboring Angle, Saxon, Jutean and, somewhat later, British tribes, to exploit internal strengths relative to their neighbors, take advantage of external opportunities overlooked by the others, and to heal or hide weaknesses while avoiding threats to the welfare of the clan.

There are several important historical questions regarding the Wicken.

- Accepting the existence of the Wicken on the Continent, is the place-name evidence of their co-location with the Angles - at one point close to Angeln, - sufficient to establish their connection to the Angles? Is there other evidence of this connection?

- What exactly was this connection? Were the Wicken a separate tribe affiliated with the Angles, or one of several (or many) Anglian subtribes, clans, or extended family groups?

- Another important question about the history of the Wicken is how was it that they were able to survive through all their migrations, to maintain their separate identity?

- Were the Wicken the same people as the Hwicce?

- If so, how and when did several families split off from the rest to move deep into the Weald?

- How did they and end up establishing a Kingdom located so far to the West. Did they follow the Thames River?

- How did they manage to move so far West and then settle between the Saxons (West Saxons, South Saxons and East Saxons) to the south, the Angles (East Angles, Middle Angles, to the north, the British tribes to the west, and the Jutes back east in Kent?

- Were the Hwicce a ruling minority within the Kingdom that also included members of Saxons and British tribes?

- How did the Kingdom of Hwicce get absorbed into Mercia?

II. THE ANGLO-SAXON SETTLEMENT OF BRITAIN [This commentary is adapted from several sources including a Wikipedia article on the topic, accessed in June 2020.]

The settlement of Britain by the Anglo-Saxon tribes was not the result of a sudden, successful invasion as was the attack by Roman legions in 43, the arrival of the great Danish army in 865, or the Norman Invasion in 1066. According to Blair (p. 30-31), the traditions and particularly the narrative of Gildas suggest that there were three distinct phases leading to the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain.

Phase I. Beginning around 410, the first phase included a period of adaptation to the conditions resulting from the reduction of the Roman armed forces in Britain, the subsequent employment of Germanic mercenaries, who rebelled and with reinforcements from the Continent, overran much of the country, until the British forced them back to Kent and East Anglia. [The Wicken may have participated in this phase as mercenaries and rebels and subsequently have settled in Kent.]

Phase II. Beginning around 500, the second phase, introduced by the British victory at Mons Badonicus, was one of equilibrium and it lasted nearly three-quarters of a century. [Some of the Wicken may have established a den in the Weald of Kent.]

Phase III. Beginning around 571, the third phase begins with a the beginnings of an English movement to recover territory which they had first penetrated in the fifth century. Battles between the British and Anglo-Saxons lasted from then until 838, four centuries after the end of Roman rule and the first arrival of Anglo-Saxon mercenaries, when the British of Cornwall were defeated by Egbert at Hingston Down. [The Wicken may have participated in battles in the south midlands where they established what was known as the Kingdom of Hwicce.]

The End of Roman Rule - By 400 AD, southern Britain – that is Britain south of Hadrian's Wall – was a peripheral part of the western Roman Empire, occasionally lost to rebellion or invasion, but until then always eventually recovered. Around 410, Britain slipped beyond direct imperial control into a phase which has generally been termed "sub-Roman". This was what the English historian Bede thought, writing in 731. According to Wood (p. 71), it fits well with scanty evidence from nearer the time, such as the fifth-century Byzantine historian Zosimus, who describes the Emperor Honorius in AD 410 refusing a formal request for military aid from local city authorities in Britain, and supported by a sixth-century writer, Procopius. Life in some cities of Roman Britain may have remained prosperous, according to archeological evidence and the description in the Life of St Germanus of Auxerre of a visit of the saint to St Albans in 429. However, conflict between constituent tribes must have arisen over the next twenty years, because according to traditions preserved in Nennius' History and in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it was internecine warfare which led to the hiring of Germanic mercenaries to fight for both sides. It is the British Gildas who adds to this rather scant picture.

Gildas, De Excido et Conquestu Britanniae (c. 540)

Gildas was a 6th-century British monk best known for his scathing religious polemic De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain), which recounts the history of the Britons before and during the coming of the Saxons. The Excidio is the only substantial source for history of this period written by a near-contemporary, although it is a polemic and not intended to be an objective chronicle.

The Excidio - The work is a sermon condemning the acts of his contemporaries, both secular and religious. The first part consists of Gildas' explanation for his work and a brief narrative of Roman Britain from its conquest under the Roman Principate to Gildas' time. He describes the doings of the Romans and what he calls "the Groans of the Britons," in which the Britons make one last request for military aid from the departed Roman military. He excoriates his fellow Britons for their sins, while at the same time lauding heroes such as Ambrosius Aurelianus, whom he is the first to describe as a leader of the resistance to the Saxons. He mentions the victory at the Battle of Mons Badonicus, a feat attributed to King Arthur in later texts, though Gildas is unclear as to who led the battle.

The Coming of Saxon Mercenaries - Gildas' narrative describes the Britons as being too impious and plagued by infighting to fend off the Picts and Scots. They managed some successes against the invaders when they placed their faith in God's hands, but they were usually left to suffer greatly. Gildas mentions a "proud tyrant" who Bede names as Vortigern as the person who originally invited Germanic mercenaries to defend the borders, but the identification of this actual historical person has not yet been firmly established. Gildas mentions that sometime in the 5th century, a council of leaders in Britain agreed that some land in the east of southern Britain [probably the island of Thanet] would be given to the Saxons on the basis of a treaty, a foedus, by which the Saxons would defend the Britons against attacks from the Picts and Scoti in exchange for food supplies. The most contemporaneous textual evidence is the Chronica Gallica of 452, which records for the year 441: "The British provinces, which to this time had suffered various defeats and misfortunes, are reduced to Saxon rule."] This is an earlier date than that of 451 for the "coming of the Saxons" used by Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, written around 731. It has been argued that Bede misinterpreted his (scanty) sources and that the chronological references in the Historia Britonnum yield a plausible date of around 428.

Since many different Germanic tribes were part of the westward migration and emigration to Britain and since there is evidence of Wicken settling in Thanet as well as their establishing a line of defense from settlements in Canterbury up through Cambridge to the Fenland, it is not unlikely that these Wicken may have been among the warrior groups who sailed to Britain and fought as mercenaries against the Picts and Scots or perhaps against some British enemies of Vortigern and then invited other family members to settle with them at this time.

The First Anglo-Saxon Raid to the West - According to Holmes, "Both Nennius and Gildas agree that Vortigern made a bargain with the Saxons. He promised to grant supplies and in return he required the Saxons 'to fight bravely against his enemies' (Nennius) or 'to fight for our country' (Guildas). It seems that the Saxons kept their part of the bargain - there were no further successful Pictish raids. Again, both Nennius and Gildas agree that the British broke the agreement by withholding the supplies. This action was a major error of judgment on Vortigern's part, for the consequences were disastrous.

...[Gildas] reports that the Saxon response was to threaten to 'plunder the whole island unless more lavish payments' were made. No supplies were received and the threat was put into immediate practice. There follows a graphic account by Gildas of the terror and devastation which resulted from the great raid of the Saxons, which penetrated almost to the west coast of the island ... He records: 'All major towns were laid low ... the foundation stones of high walls and towers had been torn down ... there was rarely to be seen grape-cluster or corn-ear'" (Holmes, p. 63).

This revolt marks the start of the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain. Assuming that some Wicken warriors had joined the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries and crossed the Channel when Hengest and Horsa first were invited to Britain by Vortigern, they were probably involved in the raid. If so, they may have traveled for the first time to the west of London where the Kingdom of Hwicce was eventually to be established. It is also possible that after this first revolt, some Wicken traveled across Kent from Canterbury and established settlements in the Weald, including the Wicken den in Cowden near the southwest border of Kent.

The Kentish Battles - The British mounted a response to the great raid with Vortigern and his son Vortimer besieging the invaders three times in the island of Thanet. Thereafter, Nennius reports and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle implies that Hengist again took the initiative and advanced westward across Kent in three battles at Aylesford, where Horsa was killed, Crayford, and Wippedfleet (possibly just south of London). According to Nennius, Vortimer died soon after and following treachery at a peace conference called by Hengist, further territorial concessions were forced on Vortigern. Once again, the Wicken, especially those living at the time in Kent, may have been involved in some of these battles.

Mons Badonicus and the Peace - According to Wood, Gildas "is our only reliable source for these events. With Vortigern dead, the British organized resistance against the invaders. Under the leadership of Ambrosius they fought a number of successful battles culminating in a great victory in the 490s, at a place called Badon Hill. This battle, says Gildas, gave forty years of peace to Britain, though, as he wrote in the 530s or 540s, 'not even at the present day are the cities of our country inhabited as formerly; deserted and dismantled they lie neglected until now, because although wars with foreigners have ceased, domestic ward continue.' Gildas does not name the British leader at Badon; as we shall see, it is considerably later traditions which insist that he was Arthur" (p. 45).

After the revolt, the great raid, and the war of the Saxon Federates, which ended shortly after the siege at 'Mons Badonicus', the Saxons went back to "their eastern home". Gildas calls the peace a "grievous divorce with the barbarians". The price of peace, Higham argues, was a better treaty for the Saxons, giving them the ability to receive tribute from people across the lowlands of Britain. They also may have invited more of their kinsfolk to join them from the Continent. Scholars have not reached consensus on the number of migrants who entered Britain in this period. Härke suggests that the figure is around 100,000, based on the molecular evidence. But, archaeologists such as Christine Hills and Richard Hodge] suggest the number is nearer to 20,000. By around 500, the Anglo-Saxon migrants were established in southern and eastern Britain.[37]

More Wicken may have migrated to Britain and participated in the struggles against the British before and after moving back east following the defeat at Mons Badonicus. They may have settled at various locations along the south shore of the Thames, with some settling near the border of the first Anglo-Saxon settlements at the Medway River. From this location other Wicken may have moved further south, eventually establishing a den deep in the Weald where Kent met the territory of the South Saxons in Sussex and the southern contingent of the Middle Saxons in Surrey.

Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People (c. 731) [This commentary is adapted from several sources including Anglo-Saxon England, an Introduction by Peter Hunter Blair ( ) and a Wikipedia article on the topic, accessed in June 2020.]

Bede, also known as Saint Bede, Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable, was an English Benedictine monk at the monastery of St. Peter and its companion monastery of St. Paul in the Kingdom of Northumbria of the Angles. This work, written originally in Latin, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between the pre-Schism Roman Rite and Celtic Christianity. It is considered one of the most important original references on Anglo-Saxon history and has played a key role in the development of an English national identity. It is believed to have been completed in 731 when Bede was approximately 59 years old.

Bede believed that the invaders of Britain had come from three of the more powerful peoples of Germania, that is from the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes. From the Saxons, that is from the district which in his day was called the land of the Old Saxons, had come the East Saxons, the South Saxons, and the West Saxons. From the Angles, that is from the country called Angulus which lay between the land of the Saxons and the Jutes and which had lain deserted ever since, came the East Anglians the Middle Anglians, the Mercians and the Northumbrians. And from the Jutes came the people of Kent, the Isle of Wight and the coastal area of Wessex opposite Wight" (Blair, p. 7).

Bede incorporated into his Ecclestiastical History almost all of the tradition told by Gildas, but with certain important modifications. He gave the name Vortigern to the man whom Gildas called simply superbus tyrannus. He also said that the leaders of the Saxons whose help Vortigern enlisted, were two brothers called Hengest and Horsa, and that Horsa was buried in Kent (Blair, p. 16). According to Bede, when the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries turned on the British, they devastated the countryside and towns:

None remained to bury those who had suffered a cruel death. A few wretched survivors captured in the hills were butchered wholesale, and others, desperate with hunger, came our and surrendered to the enemy for food, although they were doomed to lifelong slavery even if they escaped instant massacre. Some fled overseas in their misery; others, clinging to their homeland, eked out a wretched and fearful existence (Hibbert, p. 29).

Nennius, History of the Britons (c. 830) [Information adapted from Holmes and Wikipedia.]

The most detailed story about Hengist is found in a later work called the Historia Brittonum, sometimes known by the name of one of its editors, Nennius. In this work, Hengest and his brother Horsa are represented as exiles who were given land in Thanet against a promise to fight Vortigern's enemies. Later they sent for reinforcements which arrived in sixteen ships bringing with them Rowena, Hengest's daughter, who married the British king.

Nennius also provides invaluable information about Vortigern "who 'was under pressure from fear of the Picts and Scots, and of a Roman invasion, and, not least, from dread of Ambrosius'. This statement is most useful, linking, as it does, British history with three important factors which Vortigern had to consider: first, barbarian invasion: second, Roman affairs; and, third, internal politics. These three factors can be correlated with reliable historical records to substantiate Nennius' account.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (c. 890) [This commentary is adapted from several sources including a Wikipedia article on the topic, accessed in June 2020.]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is the single most important source for the history of England in Anglo-Saxon times. Without the Chronicle and Bede's the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (see above), it would be impossible to write the history of the English from the Romans to the Norman conquest. It is clear that records and annals of some kind began to be kept in England at the time of the earliest spread of Christianity, but no such records survive in their original form. Instead they were incorporated in later works, and it is thought likely that the Chronicle contains many of these. The history it tells is not only that witnessed by its compilers, but also that recorded by earlier annalists, whose work is in many cases preserved nowhere else.

English tradition about the invasions is preserved in the A text of the Chronicle. According to the Chronicle, Hengist and Horsa arrived in 449 at Ebbsfleet in the parish of Minster in the Isle of Thanet ‘in aid of the Britons,’ with a few followers in three ships. However, the annals of the Chronicle are not concerned with the coming of the Saxons but with the events leading to the establishment of kingdoms in south-east England. They begin with entries relating to battles fought by Hengest, Horsa, and Aesc between 449 and 473, continue with a series of entries relating to battles fought by Aelle and his three sons and continue further relating battles fought by Cerdic and Cynric. According to traditions preserved in Nennius' History and in the Chronicle, it was internecine warfare which led to the hiring of Germanic mercenaries to fight for both sides. D.J.V. Fisher cites archaeological evidence of settlements by Angles direct from Schleswig, "which began before the end of the fourth century and is interpreted as evidence of considerable settlement of federate type, designed and permitted to assist in guarding the cantonal town, its provincial governors and its provincial treasury against the dangers of the time." He notes an earlier detachment of Alemanni from the middle Rhine in 367 and writes that "this may not have been an isolated instance of the use of German troops and it is possible that in late Roman times the garrisons of the east coast forts were largely Germanic in composition" (Fisher, p. 15). Fisher concludes that "Anglo-Saxon tradition, retailed by Bede and supported by the Kentish king list in the 'A' version of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, was of a settlement in the middle of the fifth century; the Chronicle records the establishment of the kingdom of Kent by Hengest, his brother Horsa and his son Aesc between 449 and 473. These facts suggest that the Saxon mercenaries were first settled in Britain some years before 446" (Fisher, p. 17).

Fisher summarizes the facts that emerge from the combined evidence of the historical documents and archaeological findings: "The Anglo-Saxons came as war bands under military leaders; it is generally believed that these companies were small in number and uncoordinated in their activities., but it is possible that there may have been some larger tribal groups which arrived under the leadership of kings. They were agriculturalists concerned to find lands for cultivation and settlement, and sufficiently skilled to adapt their farming practices to the nature of the terrain. Their economic and administrative arrangements were of a nature which made towns unnecessary. In religion they were pagan....The poem Gododdin, written in about 600, tells how an elite force of Celtic warriors fought against the Anglo-Saxons at Catterick. Wearing their gold collars they prepared for the battle by feasting and drinking from gold cups; they fought to the death... Such a company Beowulf might have led to battle" (Fisher, p. 51).

Beowulf (c. 1000 AD), the Finnesburg Episode [Most of the following commentary has been extracted from articles on Beowulf and on the Finnesburg Fragment in Wikipedia accessed in June 2020.]

The Finnesburg Episode is a story (about Hengest) within a story (about Beowulf) within a story (about the Kingdom of Hwicce). Beowulf is an Old English epic poem. It may have been composed during the first half of the eighth century by a native of what was then called West Mercia, situated in the Western Midlands of England where the Kingdom of Hwicce was located. This story describes Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, one of many Scandinavian tribes), who travels to kill monsters for the Danes and then, back as King of the Geats, single-handedly kills a dragon, but perhaps due to the lack of courageous companions is mortally wounded and dies. The context for the action is a conspicuous, circuitous, and lengthy depiction of the Geatish-Swedish wars, for which reason it is considered to be an indictment of inter-generational feuding conflicts and the importance of courage, cooperation, and heroic action.

This theme is relevant for the Hwicce, who were one of several tribes fighting for territory in the area where the poem was written. Beowulf was probably a transcription of popular oral tales written down by a Christian monk living in a local monastery. A perennial human problem, feuding among various tribal groups (Anglo, Saxon and British, including the Hwicce) was certainly a major concern for the people of middle England. Overcoming those conflicts lead to the development of the five earldoms of Mercia in the ninth century (including the Kingdom of Hwicce), merger of some of these into the Kingdom of Mercia and, eventually, the unification of these kingdoms into the nation of England.

In the middle of this story, at a feast in celebration of Beowulf's recent exploit, is another story, known as the Finnesburh Episode, told by a court poet or scop. It concerns another feud between tribes, this one being an ongoing conflict between the between Danes and Frisians in Migration-Age Frisia (400 to 800 AD). During a surprise attack of the Frisians on the Danes described as Fres-wæl ("Frisian slaughter"), Hnaef, leader of the Danes, is killed and is mourned by Hildeburh, Hnæf's sister. Hildeburh had been married to Finn, leader of the Frisians, in an effort to make peace between the two tribes. In the aftermath of a surprise attack , the surviving hero, named Hengest, pledges a firm compact of peace with Finn, leader of the Frisians. But then, overcome by vengeance, he slaughters the Frisians and their leader, Finn, in their own mead hall, loots the hall, and returns with Hildeburh to their homeland.

The reason for combining this story with that of Beowulf is yet a third story. It may simply be to reiterate the themes of tribal conflict, heroism and tragedy. However there is another version of this episode that survives in the Finnesburg Fragment, a piece of a longer poem that tells of the same conflict but, significantly, does not mention either Hengest or Hildeburh. These differences suggest that the the relevance of Hildeburh to the Hwicce may be in part to demonstrate that intermarriage between tribes can create tragic conflicting loyalties and therefore that this strategy may not be enough to overcome tribal feuding. More importantly, however, is the other reference, for a person by the name of Hengest, together with his brother Horsa, was thought to have led the migration of the Angles and Saxons to Britain, to have fought successfully first, as mercenaries for the British against the Pics and then, as enemies against the British themselves to establish the Kingdom of Kent and begin efforts to push the border of Anglo-Saxon settlements westward.

Of course, while the Hwicce may have participated in these first migrations, they, together with other Anglo-Saxon tribes, would have cherished reminders of Anglo-Saxon heroes and their victories on the continent because, while they were eventually victorious in settling and ruling over England, this was only after they were defeated in a series of battles by the British under a leader like Finn. Interestingly, this leader, or a successor like him, was celebrated much later in story and legend as King Arthur.

Collectively, these stories, legends and historical accounts serve to illustrate the violence and savagery practiced by at least some of the Anglo-Saxon invaders. However, it should be noted that while Gildas' mentions "Hengist and Horsa" in his History, some historians believe this suggests that the actual origin of "Saxons" in Britain had already fallen into myth. Gildas writes as if they are real people, yet historians now interpret these names as a military tradition, like "Romulus and Remus," not an actual genealogy. Gildas' metaphors of the collapse of the British also need to be interpreted in the context of the Justinianic plague, which halved the population of Europe around 550 CE, the time he was writing. Metaphors commonly interpreted to mean invading Saxons could actually be referring to plague sweeping across the land.

Ambrosius Aurelianus and King Arthur [The following was mostly adapted in June 2020 from an article in Wikipedia on King Arthur.]

The battles that followed the early emigration of Anglo-Saxons to Britain are suggested in the documents and legends that have arisen since that time, centered primarily on the figures or Ambrosius Aurelianus and King Arthur.

Ambrosius Aurelianus was a war leader of the Romano-British who won an important battle against the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th century, according to Gildas. He also appeared independently in the legends of the Britons, beginning with the 9th-century Historia Brittonum of Nennius. De Excidio is considered the oldest extant British document about the so-called Arthurian period of Sub-Roman Britain. Following the destructive assault of Saxons, the survivors gather together under the leadership of Ambrosius, who is described as:

a gentleman who, perhaps alone of the Romans, had survived the shock of this notable storm. Certainly his parents, who had worn the purple, were slain in it. ...Under him out people regained their strength and challenged the victors to battle. The lord assented, and the battle went their way.

Nennius contains the first datable mention of King Arthur, listing twelve battles that Arthur fought. These culminate in the Battle of Badon, where he is said to have single-handedly killed 960 men. Recent studies, however, question the reliability of the Historia Brittonum. The other text that seems to support the case for Arthur's historical existence is the 10th-century Annales Cambriae, which also link Arthur with the Battle of Badon. The Annales date this battle to 516–518, and also mention the Battle of Camlann, in which Arthur and Medraut (Mordred) were both killed, dated to 537–539. These details have often been used to bolster confidence in the Historia's account and to confirm that Arthur really did fight at Badon.

Problems have been identified, however, with using this source to support the Historia Brittonum's account. The latest research shows that the Annales Cambriae was based on a chronicle begun in the late 8th century in Wales. This lack of convincing early evidence is the reason many recent historians exclude Arthur from their accounts of sub-Roman Britain. Still, there are others like Geoffrey Ashe who write of the discovery of King Arthur based upon a reconsideration of the evidence. Regardless of the historicity of Hengist and Horsa, Aurelianus and Arthur, it is certain that there were many battles between and among the Anglo-Saxon and British tribes following the emigration of the former from the continent. The Wicken were likely a part of this emigration and therefore participants in at least some the battles that occurred in Kent and the southern midland areas of Britain during this time.

The Kingdom of Hwicce (c. 577-805) [A wonderfully detailed account of the formation of the Kingdom may be found at KINGDOM OF HWICCE.]

The Hwicce (or Hwicca) emerged from obscurity, probably from within territory controlled by the West Seaxe, to form their own kingdom. The British kingdoms based on Caer Gloui (Gloucester), Caer Ceri (Cirencester) and most of Caer Baddan (Bath) were overrun in a large-scale Saxon attack in 577 and their last kings killed in battle. The people who formed the Hwicce took the opportunity to move into this territory and settle, with communities centred on Gloucestershire and Worcestershire that were apparently independent of the West Seaxe.

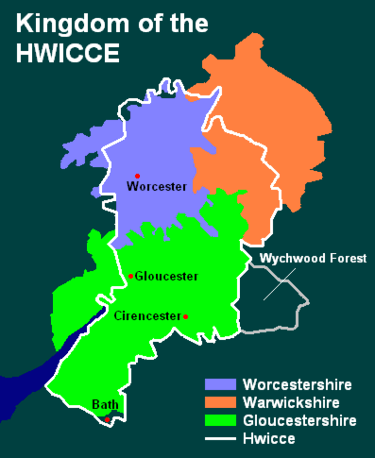

The precise dimensions of the kingdom are unknown but they probably coincided with those of the old diocese of Worcester, the early bishops of which bore the title Episcopus Hwicciorum. It would therefore include Worcestershire, Gloucestershire except the forest of Dean, the southern half of Warwickshire, and the neighbourhood of Bath as far as the River Avon. The name Hwicce survives in Wychwood in Oxfordshire ('hwicce-wood', on the eastern edge of the kingdom), Whichford in Warwickshire, and the Wychavon district of Worcestershire. Just nine kilometres or so to the north-east of Worcester is a tiny hamlet called Phepson. This records the group of settlers whom Bede called the Feppingas. To their south, the Wixan left their name in the form of the Whitsun Brook. Another group were the Stoppingas. The Tomsaetan are sometimes grouped with the Hwicce, but they were essentially Mercians, probably being one of the earliest groups to be conquered by the Iclingas.

No genealogy or list of kings has been preserved, and it is not known whether the possible rulers of the Hwicce were connected to the West Saxons or the Mercians. It seems likely that the rulers of the Hwicce did not appear until after conquest by Mercia in 628. It is even possible that it was not one united territory until then, more a series of colonies with close trading and/or political links. Instead, Ceawlin of the West Saxons probably dominated until the Mercian conquest.

Interestingly, the Hwicce played a key role in the initial conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. According to the Wikipedia article, in 603 the first meeting takes place between the Roman Church in the form of St Augustine of Canterbury, and the British/Celtic Church (the descendant of the former British Church of the Roman period). It is arranged when Æthelbert of the Cantware uses the Hwicce as intermediaries, as they possess a church organisation which seems to have survived intact from prior to the Saxon takeover of the region (and probably a ruling elite, although this is not mentioned and no records survive of the names of any rulers from this period). The meeting occurs at a place which Bede names as St Augustine's Oak, on the border between the Hwicce territory and that of the West Seaxe (somewhere on the eastern slopes of the Cotswolds, perhaps near Wychwood, 'Hwiccas' wood', in Oxfordshire). The meeting goes favourably well for Augustine.

From 805, the Hwicce lose any independent control of their lands to Mercia, during the reign of Coenwulf. The Mercian kings assume the title 'ealdorman of the Hwicce'. When Mercia fails as an independent kingdom in the face of the great Danish army of the 870s, the title passes to the royal house of Wessex which rules the surviving free half of the kingdom as the Lords of Mercia. Hwiccan identity gradually fades out of use.

Tribal Hidage (c. 657-74?) [The following was mostly adapted from Michael Wood's book on Domesday (1986, BBC Books).]

The Tribal Hidage - The Tribal Hidage is a tribute list drawn up from a Mercian viewpoint that is very important in reconstructing early English geography. It is a list of early tribes, largely of the Midlands, from before the time the country was divided into shires. According to Michael Wood any one of several Mercian kings might have initiated it;

The great kings of the eighth century, Aethelbald and Offa, have inevitably been suggested, as they are known to have claimed overlordship of the English peoples south of the Humber. The Hildage, however, has a very archaic feel and may date from one of the earlier Mercian rulers, perhaps Wulfhere (657-74). Many of the folk names in the list may have ceased to be used in the later period, though it is known that the five earldoms of Mercia in the ninth century were of the Mercians, the Middle Angles, Lindsey, the Hwicce, and the Magonsaeten (Westerna?). While the terms Hwicce and Nagonsaeten continue to be used as regional and even administrative divisions into the eleventh century. ...

From the details of the Tribal Hidage it can be seen how long before Domesday, a system of tribute and taxation was imposed on the whole of England south of the Humber - a system based on the same unit used by the Conqueror's survivors in 1086 (Wood, p. 88-89).

Taxation at the time of the Tribal Hidage was based upon "hidage," the unit of which is the "hide." As is mentioned by Bede, districts were composed 'according to the English custom' of so many units of 'land for one family.' Thus "hide" was meant to be the amount of land which could support one peasant family. In the Hidage, the land of

- the Hwicce is listed at several thousand hides, whereas

- the Mercians is listed at 30,000 hides, 10 times as much, and

- Cantawarena [Kent] is listed at 15,000 hides, 5 times as much.

It is clear from the Hidage and other sources that the Hwicce were well-established in the southwestern midlands of England and came to exert leadership over an area known as the Kingdom of Hwicce. (See the page on A Side Trip to the Kingdom of Hwicce for more detail.) Given their relative size it is no wonder that the Hwicce were eventually absorbed into Mercia!

IV. The Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest [The following was mostly adapted in June 2020 from an article in Wikipedia on Norman Conquest of England.]

In 1066 England was invaded and occupied by an army of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French soldiers led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conqueror. When King Edward died at the beginning of 1066, the lack of a clear heir led to a disputed succession in which several contenders laid claim to the throne of England. Edward's immediate successor was the Earl of Wessex, Harold Godwinson, the richest and most powerful of the English aristocrats.

After King Harold had successfully put down several other challengers, William assembled a large invasion fleet and an army gathered from Normandy and all over France, including large contingents from Brittany and Flanders. He mustered his forces at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme. A contemporary document claims that William had 726 ships, but this may be an inflated figure. Modern historians have offered a range of estimates for the size of William's forces such as 7000–8000 men. The army would have consisted of a mix of cavalry, infantry, and archers or crossbowmen, with about equal numbers of cavalry and archers and the foot soldiers equal in number to the other two types combined.

The Normans crossed to England on 25 September, a few days after Harold's victory over the Norwegians at Stamford Bridge and following the dispersal of Harold's naval force. They landed at Pevensey in Sussex on 28 September and erected a wooden castle at Hastings, from which they raided the surrounding area. This ensured supplies for the army, and as Harold and his family held many of the lands in the area, it weakened William's opponent and made him more likely to attack to put an end to the raiding. Pevensey is 33 miles from Cowden, Kent, and Hastings is 36 miles. Cowden may have been too far and too small for William's troups to raid. It is more likely that if they traveled that far, they would have raided the larger town of Tonbridge, 32 miles to the north.

Leaving on October 11th, Harold marched his men down toward Hastings from London, probably by way of Tonbridge, which is only 11 miles from Cowden. He took up a position at present-day Battle, East Sussex, about 6 miles from William's castle at Hastings. At 9 am on 14 October 1066, William advanced towards King Harold and the battle lasted all day. Harold and his brothers were killed and as darkness fell the remnants of the English army broke and fled. The following day, King Harold's body was identified. The dead were left on the battlefield, except for some of the English who were removed by relatives later. The decisive battle which marked the end of the Anglo-Saxon state and the beginning of the Norman Conquest had been fought and lost. William advanced along the coast (away from Cowden) toward London and continued fighting until the English surrendered. He was acclaimed King of England and crowned by Ealdred on 25 December 1066, in Westminster Abbey.

Contemporary sources do not give reliable data on the size and composition of Harold's army, but most recent historians agree on a range of between 7000 and 8000 English troops. These men would have comprised a mix of the fyrd (militia mainly composed of foot soldiers) and the housecarls. Since much of Harold's army was left up north near Stamford Bridge, it's possible that local troups may have traveled south with the King or that additional troups may have been hastily recruited from the manors around Kent, but this is unlikely. So, if any Wickendens were providing Knights Service to the king at that time, it is likely that they were involved in the fighting. Even if not serving as combatants, they certainly heard about the battle by word of mouth, since the movement of thousands of troups and the battle that resulted in hundreds of dead left unburied on the field and which ultimately changed the course of English history, all this took place less than half a day's walk from the homestead of Wickenden in the village of Cowden.

The Domesday Book (1086) [The following was mostly adapted in June 2020 from an article in Wikipedia and the book by Michael Wood.]

Formally known as the "Great Inquisition or Survey of the lands of England, their extent, value, ownership, and liabilities, made by order of William the Conqueror in 1086," the Domesday Book was a report of a survey conducted by William the Conqueror in 1085 of the estates or manors throughout the middle and southern portion of England. The book was called ‘Domesday’ as a metaphor for the day of judgement, because its decisions, like those of the last judgement, were unalterable. As reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

Then, at the midwinter [1085], was the king in Gloucester with his council ... . After this had the king a large meeting, and very deep consultation with his council, about this land; how it was occupied, and by what sort of men. Then sent he his men over all England into each shire; commissioning them to find out "How many hundreds of hides were in the shire, what land the king himself had, and what stock upon the land; or, what dues he ought to have by the year from the shire.

The territory was divided into seven circuits, the same 20 questions were asked by commissioners of panels of representatives from the estates within each circuit. Amazingly, a second circuit was conducted the same year to verify the accuracy of the data, although this was a reflection of the distrust of the English by the Normans . One man, wrote up the entire __ page report in 1086, 20 years after the conquest in 1066. The following year King William died while leading a campaign in northern France. According to Wikipedia, most shires were visited by a group of royal officers (legati), who held a public inquiry, probably in the great assembly known as the shire court. These were attended by representatives of every township as well as of the local lords. The unit of inquiry was the Hundred (a subdivision of the county, which then was an administrative entity). The return for each Hundred was sworn to by 12 local jurors, half of them English and half of them Norman.

The Kingdom of Hwicce - Since Gloucester is in the center of what had been known as the Kingdom of Hwicce, it is not surprising that there is information in Domesday about the settlements in that Kingdom, including those whose names derive from the Hwicce. The book on Domesday by Michael Wood (1986, BBC Books) notes that Cirencester and Gloucester "fell to English warbands as late as 577, but the Cotswolds north and west of Cirencester show little evidence of early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, and it is likely that some form of Romano-British rule existed there until 577, even though the cities theselves by then were thinly populated and ruinous" (p. 56). Wood's account of the Hwicce is as follows:

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle believed that the former Roman cities of Gloucester, Bath and Cirencester were still centers of administration when they were sacked in 577; it believed that they were governed by 'kings', and the names it gives for them (Conmail, Condidan and Farinmail) look like British - or in one case (Candidanus?) Roman names. The attack of one group of Germanic invaders, the West Saxons, from the Thames valley into the Cotswolds in 577 did not lead to permanent colonisation. Subsequently a kingdom was established there under the overloadsip of another big grouping of Anglo-Saxon settler tribes: the Mercians. The folk name of this particular kingsom, the Hwicce, is still obscure, but the name 'Cotswolds' was synonymous in the Dark Ages with the 'hill of the Hwicce', and among the 'Hwicce' names which have survived into modern times is Wychwood, the forest which separated the Saxons of the Thames valley from the Hwicce.

The Hwicce ruling family were Anglian in origin, and their armed following perhaps a mixture of Angle and Saxon. But the mass of the population of what is now Gloucestershire must have been of British origin in the seventh century, and it stands to reason that many traditions from Roman times must have carried down to the English period, especially in rural areas" (p. 57)

An example of a Hwicce-related place is Withington, which was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Wacrescumbe and the county of Gloucestershire. It had a recorded population of 15.6 households in 1086 (NB: 15.6 households is an estimate, since multiple places are mentioned in the same entry). Another example is Whichenford. The manor of WICHENFORD was no doubt included at the time of the Domesday Survey in that of Wick Episcopi belonging to the see of Worcester.

The Manor of Cowden Lewisham - A summary of data from the Book provides demographic information about the territory in the south-west corner of Kent where Cowden is situated. The population included 2.5 to 5 people per square mile, it included under 5% slaves, above the English average of 40.6% of villeins (bonded peasants who pay labour service to the lord but have a share of common fields) , and no sokemen (those free to buy and sell land). While Cowden and Wickenden (one of its tenements) is not mentioned, the nearby village of Hartfield, just over the border in Sussex, was probably quite similar. Hartfield is listed with 8 households consisting of 6 villagers and 2 smallholders, and including resources of 3 ploughteams (1.5 of the Lord's and 1.5 of the men's), and other resources including 3 acres of fields and 5 acres of woods, swine rendered. By way of comparison, the largest city in Kent was Cantebury, with 262 households. Lewisham, to which manor Cowden was to be added, is listed with 62 households. Rochester is listed with only 16 households, although both Chatham (the harbor) and Strood (across the Medway River) are listed with more.

It is somewhat surprising that Cowden was not mentioned, given that, according to the Chronicle, "So very strictly did he (King William) have it investigated that there was no single hide nor a yard of land, no indeed (shame it is to relate but it seemed no shame to him to do) one ox nor one cow nor one pig was left out." It may be that subsequent exploration of Domesday will reveal Cowden to be included somewhere. Nevertheless, since the survey was used to levy a new and reportedly heavy tax, to avoid being included would seem to be one means of avoiding the tax.

IV. ENGLISH HISTORY [Historical documents relating to the Wickendens such as lists of kings, charters and census reports may be summarized here.] One of the most detailed accounts of the history of the Hwicce may be found at RULERS OF THE HWICCE.

RULERS OF KENT |

Hengist (c. 455-488) 455 - Some Wicken cross Channel as mercenaries |

Æsc (c. 488-512) 500 - Wicken settle in Kent, from Thanet to Medway River |

Octa (c. 512-540) |

Eormenric (c. 540-565) |

Aethelberht I (565-616) 600- Some Wicken establish den in Weald of Kent 603 Aethelberht arranges a meeting for St. Augustus of Canterbury and representatives of the British/Celtic church in Wychwood of the Hwicce |

Eadbald (616-640) |

Earconbert (640-664) |

Egbert I (664-673) |

Hlothere (673-685) |

Eadric (685-686) |

Wihtred (690-725) |

Eardwulf (725-?) |

Eadbert (d. c. 762) |

Æthelbert II (d. c. 762) |

Sigered (c. 762-763) |

Eanmund (c. 763) |

Heahbert (c. 764-765) |

Egbert II (fl. c. 779) |

Ealhmund (fl. c. 784) |

Eadbert (c. 793-796) |

Aethelwulf (825-839, 856-858) |

RULERS OF THE HWICCE

Eanfrith (c.650s-674)

571 - Wicken begin to settle in Southern Midlands - identified as Hwicce

603 - St. Augustine of Canterbury, representing the Roman Catholic Church meets with leaders of the British/Celtic Church at Wychwood, the border between the Kingdom of Hwicce and the West Saxons, supposedly arranged by Athelbert of the Cantwere using the Hwicce as intermediaries.

Eanhere (c.674-75)

Osric (c.675-679)

Oshere (c.679-704)

Oswald (c.685-c.690)

Ethelbert/AEthelheard (fl 700)

Ethelward/AEthelweard (fl 710)

Ethelric/AEthelric (fl 720)

Osred (fl 730s)

Eanberht (c.757/759)

Uhtred (co-ruler)

Ealdred/Aldred (co-ruler)

AEthelmund (c.796-802)

Aethelric (fl 804)

RULERS OF ENGLAND

House of Wessex

Egbert 802-39

Aethelwulf 839-55

Aethelbald 855-60

Aethelbert 860-66

Aethelred 866-71

Alfred the Great 871-99 - Built first navy; united SW England

Edward the Elder 899-925

918 - Manor of Lewisham granted by Elstrudis, the daughter of Alfred the Great and wife of Baldwin, Count of Flanders, to St. Peter's, Ghent

Athelstan 925-40

Edmund the Magnificent 940-6

Eadred 946-55

Eadwig (Edwy) All-Fair 955-59

Edgar the Peaceable 959-75

946 - Grant of Lewisham confirmed by "Edgar king of the English."

Edward the Martyr 975-78- Killed by Vikings.

Aethelred the Unready 978-1016 - Bad king: paid Dane-geld to Vikings.

Edmund Ironside 1016

Danish Line

Svein Forkbeard 1014

Canute the Great 1016-35

Harald Harefoot 1035-40

Hardicanute 1040-42

House of Wessex, Restored

Edward the Confessor 1042-66 - Sainted for his piety

1044 - Royal Charter mentions Wingindene - assigned to Lewisham, St. Peters, Ghent

Harold II 1066 Couldn't fight off Vikings and William the Bastard, below

Norman Line

William I the Conqueror 1066-87 aka Duke William the Bastard

William the Conqueror granted a fresh charter for Manor of Lewisham and added the five tenements in Cowden, including Wickenden, for pannage of swine in the forest

William II Rufus 1087-1100 murdered in "hunting accident"

Henry I Beauclerc 1100-1135

1115 - Cowden church/village mentioned in Textus Roffenssi

Stephen 1135-1154

Empress Matilda 1141 Scandalous queen.

Plantagenet, Angevin Line

Henry II Curtmantle 1154-89 Married Elanor of Aquitaine

Richard I the Lionheart 1189-99 Spent most of time crusading.

John Lackland 1199-1216 Lost most of French holdings

abt 1200 - Martin de Wiggindenn christened in Cowden, and mentioned in Archaeolingio Cantiana in Cambridgeshire - first mention of individual Wickenden

Henry III 1216-72

1283 - Polledefeld (Polefields) mentioned

Edward I Longshanks 1272-1307 Campaigned in Wales, Scotland

Edward II 1307-27 Killed as a homosexual in a coup

Edward III 1327-1377 Warlike and expansionistic.

Richard II 1377-1399 Weak-willed "poet-king."

Plantagent, House of Lancaster

Henry IV (Henry Bolingbroke) 1399-1413 Usurped throne

Henry V ("Prince Hal") 1413-1422 England's golden boy.

Henry VI 1422-61, 1470-71 Suffered from insanity

Wickendens move across Cowden

1456 - Ludwells Farm willed to Thomas Wygenden

1461 - Thomas Wykendene living in Clendene and leasing Wikenden

1476 - Richard Wickenden of Polefields in Court Baron of Cowden Lewisham Manor

1479 - Thomas Wickenden one of a homage of a Court Baron of Cowden Lewisham Manor

Plantagenet, Yorkist Line

Edward V 1483 Too short-lived to rule.

Richard III (Richard Plantagenet) 1483-1485 Known as "Richard Crookback."

1487 - Richard Wickenden executor of will of Richard Styll

House of Tudor

Henry VII (Henry Tudor) 1485-1509 Ended War of the Roses

Wickendens move beyond Cowden into Kent, Sussex and Surrey

Henry VIII 1509-1547 Broke with Catholic church

1510 - Will of Richard Wiggenden, the Elder

1512 - Henry Wydenden mentioned in Tornar will

1524 - Joan Wekynden wills homes in Cowden to sons Thomas, William and Antonye

1524 - John Wydenden included as a witness to the will

1540 - Will of Elizabeth Wickenden Gainsforth

Edward VI 1547-1553

Lady Jane Grey 1553 "Ruled" nine days. Executed.

Mary Tudor ("Bloody Mary") 1553-1558 Catholic Queen allied to Spain

Queen Elizabeth I 1558-1603 Shakespeare's early queen

1558 - Court Baron of the CL Manor attended by Thomas Wykinden de Cowden Streate

1558 - Court Baron of the CL Manor also attended by William Wickenden de Ludwells

1571 - Thomas Wickenden de Bechinwoode attended a Court Baron for CL Manor

1589 - Homage of a Court Baron for CL Manor mentions Thomas Wickenden de la hole

House of Stuart

James I (King James VI of Scotland) 1603-1625 Shakespeare's late king.

1604 - William Wickenden, the Elder, leaves house to son William

1623 - Wickenden "lost" from St. Mary Magdalene Church rolls

Charles I 1625-1642 Executed 1649 after civil war.

1626 - Ould mother Wickended of Powlfields buried

1626 - John Wickenden leased land

1636 - Richard and William Wydenden served as executors of Turners will

The Commonwealth

Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector 1642-1649 Dictator rather than king

Richard Cromwell 1658-59 House of Stuart, Restored

Charles II 1660-1685

1665 - Thomas Wickenden and other Churchwardens buy an Almshouse (5 cottages) for the poor

James II 1685-1688 died 1701

Mary II 1688-1694

Date unknown - Thos. de Wickenden gives Warefield to the Priory of Michelham to hold in capite by Knights Service

3rd and 4th year of King Philip and Queen Mary - the Queen grants to Richard Sackville and Thomas Winton, among other premises, the Manor of Cowden and appurtenances (including Wickenden) and Warefield, late in the tenure of William Wickenden descendant of Thomas Wickenden

William III + Mary II 1689-1702

House of Orange and Stuart

Anne 1702-14

Hanover Line (House of Brunswick)

George I 1714-27

George II 1727-60

George III 1760-1820 Lost the American colonies

George IV 1820-30

William IV 1830-37

Victoria 1837-1901 "We are not amused."

House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha

Edward VII 1901-10

House of Windsor

George V 1910-36 Name-change avoids Germanic

Edward VIII 1936

George VI 1936-52

Elizabeth II 1952-present Longest female reign since Queen Elizabeth I.

Return of Owners of Land (1873) (sometimes termed the "Modern Domesday")

V. AMERICAN HISTORY

1775-83 - AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR

1861-65 AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

The Pioneers - The Pioneers, tells the story of the 17th- and 18th-century settlers who set out to start lives in the Northwest Territory, the region of the country that is now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and much of the Upper Midwest. It's a fascinating look at a chapter in American history that's been somewhat neglected in the country's popular imagination.

The Pioneers begins with the story of a man named Manasseh Cutler, a New England pastor who played a key role in the passage of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which created the Northwest Territory and prohibited slavery anywhere within it. In this best-selling book award-winning historian and biographer David McCulloch uses settlers’ diaries to document how Cutler, a white clergyman and Revolutionary War veteran, and others moved to country that had been ceded to the U.S. from Great Britain after the war. As a part of the larger narrative of westward expansion, McCulloch tells the story of a group of New Englanders, led by Rev. Manasseh Cutler, who in the late 18th century ventured across the frontier into the Northwest Territory — now Ohio — to create communities. The author told The Associated Press in a recent interview that he wanted to write about people not widely known to the general public. In dramatizing the self-reliance and grit of these pioneers, McCulloch has been accused of romanticizing white settlement and downplaying the pain inflicted on Native Americans. Nevertheless, he describes these pioneers as people who set out to do something that was thought to be impossible, who ran into more complicated turns and tests of their fortune than they ever imagined or expected, and who don’t give up. The Wickendens (and the Consauls) of East Toledo and Oregon County, Ohio, might be thought of as a second wave of pioneers who brought the ideals of self-reliance, hard work, education, civic engagement, and social service with them from Rochester, Kent, England (and from Spain by way of Holland and the state of Maine) to help develop the state of Ohio.

REFERENCES

Geoffrey Ashe, The discovery of King Arthur (Anchor Press Edition, 1985).

Peter Hunter Blair, Anglo-Saxon England: An Introduction (Barnes & Nobel, 1977)

D.J.V. Fisher, The Anglo-Saxon Age, c. 400 - 1042 (Barnes & Noble, 1992).

Christopher Hibbert, The Story of England (Phaidon Press. Ltd., 1992)

C. Warren Hollister, The Making of England: 55B.C. to 1399, 5th edition (D. C. Heath and Company, 1988)

Michael Holmes, King Arthur: A Military History (Barnes & Nobel, 1996).

David McCulloch, The Pioneers, The Heroic Story of the Settlers Who Brought the American Ideal West (Simon & Shuster, 2019).

Michael Wood, In Search of the Dark Ages (Facts on File Publications 1987).

Michael Wood, Domesday: A Search for the Toots of England (1986, Basic Books).